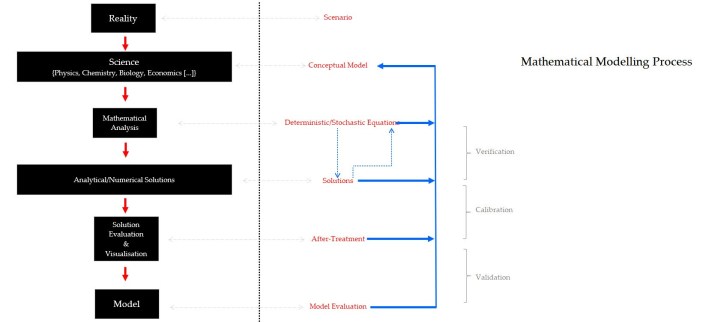

Mathematics, like grammatical language, is part of our daily lives and it’s present in virtually everything we do, even if we are not consciously aware of it. Below, I list some of the mathematical models that are pretty connected to our everyday lives.

Demand of goods and services

Maybe the most obvious and well-known. It is given by:

,

where,

: A given Good or Product

: Quantity of said Good

: Price of Good

C: Ceteris Paribus condition (i.e. keeping constant every other factor that may impact demand)

: Demand Function

: first partial derivative of the Demanded Quantity with respect to Price (rate of change of the quantity for every variation in the price).

This rate of change shows to be $latex< 0$, which indicates the well-known statement as the price increases, quantity demanded decreases and vice versa. Likewise, when there is an abundance of a given good, price tends to decrease due to its availability and “non-rarity”; but if the good is scarce then the price will go up because buyers will be willing to pay higher amounts of money to get it.

Queuing and Traffic Models

Two examples here:

- The queueing models used by customer care service in banking, telecom and, in general, any system requiring to estimate the amount of individuals that will be in queue waiting to be served by n representatives (servers) in a given period of time. These events follow a Poisson probability distribution and can be modeled using the so called Poisson processes. Poisson distribution is given by:

where,

: Number of observed events

: Average numbers of events per time interval

: Exponential Constant

: n factorial [n(n-1)(n-2)…(2)(1)]

- The network traffic models used by telephone service providers to calculate network congestion and guarantee QoS (quality of service). Traffic is usually modeled following an Erlang distribution, whose probability density function is given by the following expression:

Risk Models

They are used to estimate outcomes in several scenarios, among them the risk of granting x amount of money in loan to a given person. Also, they are used to model survival: the probability that a specific customer continues with the company after any given specified time, or that a patient survives after a future time T. Survival is modeled by:

Which is the same as to say that survival is the complementary function of the cumulative distribution function, or , where

is the cumulative distribution function

Meteorological Models

We all have seen (and experienced) weather forecasts and atmospheric phenomena follow-up models. These models, named CLIPER (climate and persistence), use Multiple Linear Regression methods to predict climate behavior.

Multiple linear regression equation is given by:

where,

: forecasted variable

: Y axis intercept; or the average constant value of a forecasted variable Y when all X values given to estimate it are equal to 0

: Regression slope; i.e., how much does the Y forecast change for every change in each X component used to predict it

: Components impacting the forecasted variable

: Estimation error

All these examples, and the ones detailed in the other answers, show that mathematical models are indeed part of our daily lives. Some may look more complex than others, but the intuition is simple and easy to follow. The important part is not the calculations per se, but the awareness that we can put mathematics to use in a lot of everyday situations and, in this way, help to demystify a bit all things pertinent to this discipline.