A Mathematical Model is an abstraction of a real-life scenario, system or event that uses mathematical language to describe and predict the behavior, dynamics and evolution of said scenario, system or event.

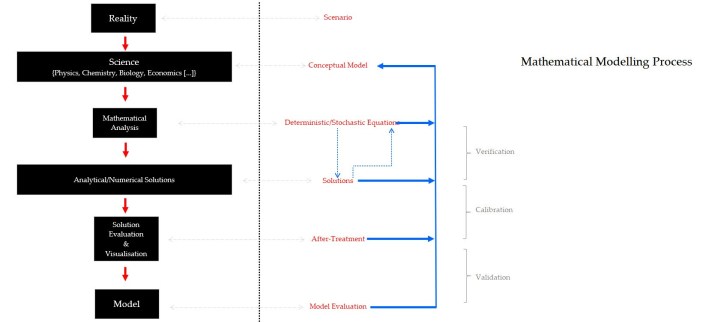

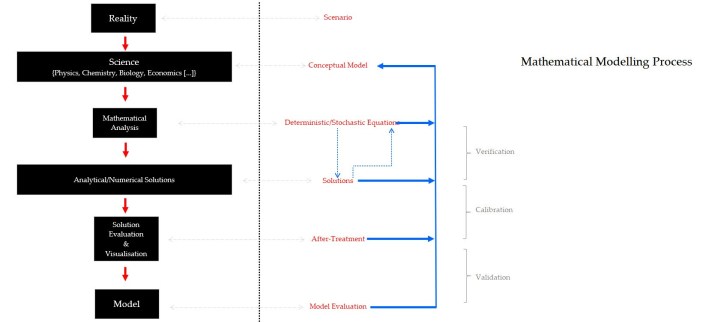

Mathematical Modelling is thus the step-by-step process of performing this abstraction from real scenarios to equations and formulas we can use to infer their characteristics. This is better visualized by the following diagram:

Reality is studied by Science and its different branches, known as disciplines. These disciplines conceptualize Reality, each in their own way within their area of study. For example, Physics and Chemistry study nature’s structure, Biology deals with living beings and Economics tries to explain production and consumption of goods and services. These conceptualizations are then formulated as mathematical equations, either deterministic (fixed) or stochastic (partially random), depending on the nature of the scenario or system.

Once the equations are formulated, they are solved to find solutions depicting the behavior, dynamics and evolution of the their real-life counterparts. Upon evaluation, these solutions may not be accurate when contrasted with observed experimental data and might need calibration and adjustment. If no progress is achieved, the process goes back one step to find a better equation defining the system.

Once the equations and solutions are verified and calibrated, the model is validated when it accurately describes Reality and its results can be shown to be reproducible and repeatable across the Scientific community.

Mathematical Models need to be reviewed from time to time to confirm if they are still relevant. As the disciplines and systems evolve, they may be updated or even replaced with new ones better depicting Reality. This is why mathematical models are at the core of the Scientific Method principle of falsifiability, providing a direct way to evaluate solutions, update descriptions and create new theories.

but…

Why do we use abstract mathematical models when we could develop physical models?

Abstractions are good because they generalize patterns, behaviors, outcomes and realities without having to physically construct a model. Even if you develop a physical model, which is very good to actually see how a system outcome would look, it wouldn’t say much about the inner rules governing that system.

In general, Nature already has a physical model constructed for us called Reality and we just want to know how to predict the behavior and outcome of the systems that form that Reality.

Let’s take our Solar System for example. We could build a replica one trillionth its actual size and sure enough you will have accurately depicted the size of the planets and the Sun, the length between them, their moons and their orbits. If we throw in an incandescent bulb with the appropriate power and placing it within the Sun, we will also have shown irradiance and even the temperature of the Solar System space, but the keyword here is shown. We could continue to add as many features as humanly possible to the model, to make it as accurate as the real thing, but the fact remains we are are only describing a steady state: we are not actually gaining any insight about the dynamics of the system, we are not exploring how variables interact with each other and how internal conditions can affect its outcome. Furthermore, we cannot make predictions at all, because we don’t have a general abstraction that receives inputs, process them and then gives us back the output of the system variables.

Physical models need to be used in tandem with mathematical models if we are to derive some concrete insight from them. Now, let’s imagine we have an aeronautical engineer and we need to simulate a plane’s behavior at a given altitude, subjected to X pressure and Y air velocity, among other things. Our engineer proceeds to build a physical model of the plane and a wind tunnel to test air dynamics and how it interacts with your scaled-down model. She puts the plane model inside the tunnel, turn on the wind simulation (fan) and then with the aid of a mathematical model (Bernoulli’s principle, Reynolds number and Mach number in this case) she makes the necessary adjustments to guarantee the optimal production of a real sized plane.

Image Source: Wikipedia

Without the actual mathematical model, it would not be possible to make efficient adjustments. Imagine if we always had to build a physical model for everything we wanted to describe, or if we had to build several models for every scenario we wanted to extract information from. Besides the time, effort and financial cost, the models wouldn’t be able to tell us much, apart from a good visual representation. Even prototypes are built after doing the math and not the other way around, to optimize the above mentioned factors.

The good news are that recent advance in computational simulation is rendering the need of using a physical model unnecessary in many areas, while in others they are continued to be used together with the computer simulated/mathematical models; such as in the case of our wind tunnel example in the field of Aerodynamics.